NANDINI ROY CHOUDHURY

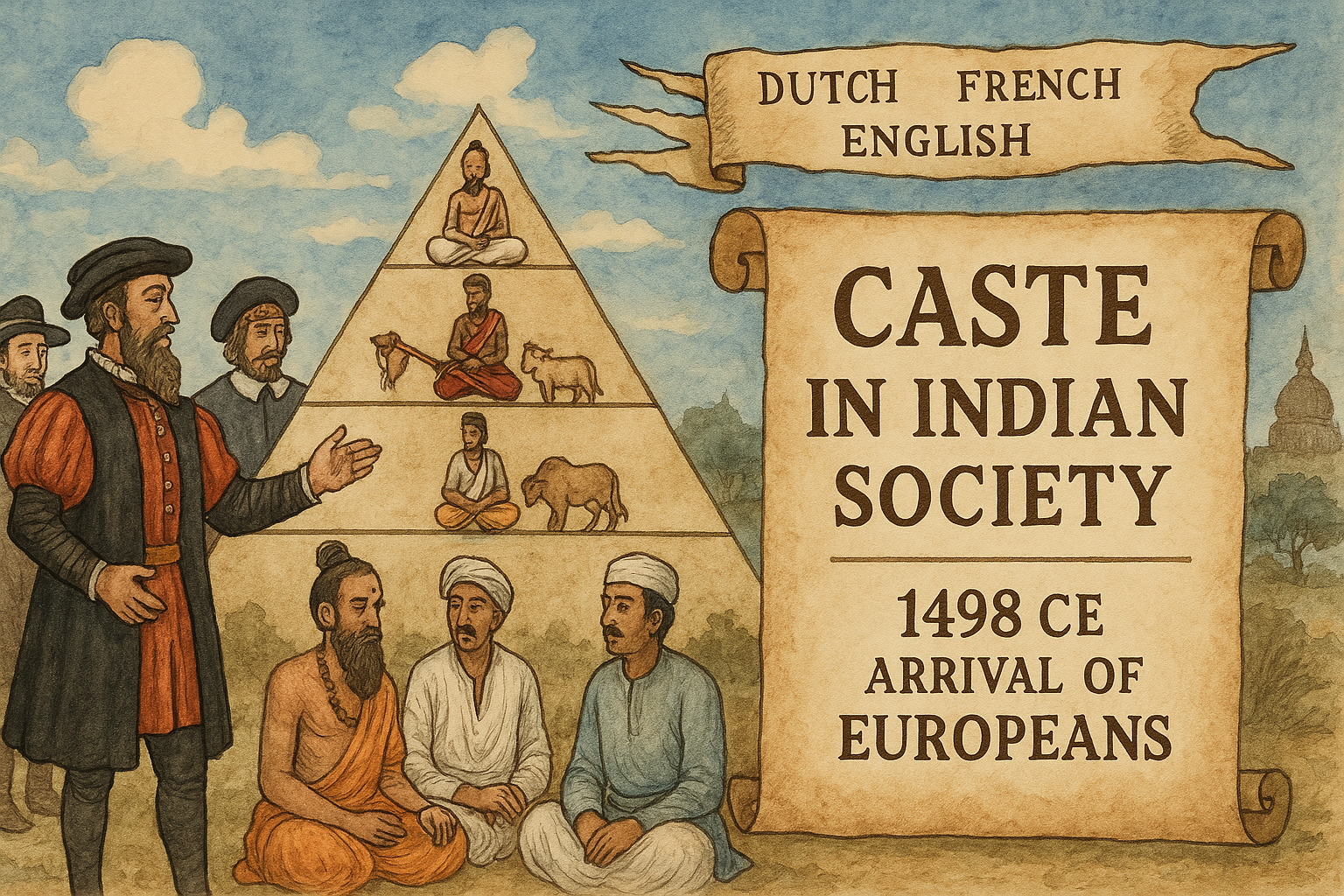

The year 1498 CE marks a significant milestone in Indian history with the arrival of Europeans, led by Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama. Following their lead, other European powers: Dutch, French, and English, established commercial ties with the subcontinent. For these settlers, understanding Indian society, culture, and hierarchical structures was essential for commerce. Thus, ‘caste’ became the primary symbol representing Indian society. Exposure to local narratives led to the belief that caste was a rigid, complex system of hierarchy, dating back to Rig Vedic times.

The year 1498 CE marks a significant milestone in Indian history with the arrival of Europeans, led by Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama. Following their lead, other European powers: Dutch, French, and English, established commercial ties with the subcontinent. For these settlers, understanding Indian society, culture, and hierarchical structures was essential for commerce. Thus, ‘caste’ became the primary symbol representing Indian society. Exposure to local narratives led to the belief that caste was a rigid, complex system of hierarchy, dating back to Rig Vedic times.

However, the term ‘caste’ is not indigenous; it derives from the Portuguese word casta. Over time, amid the struggle for power, the British emerged dominant. Their involvement in Indian economy, politics, and administration necessitated a thorough understanding of pre-existing institutions. To facilitate governance, British officials, ethnographers, anthropologists, and historians such as H.H. Risley, W.W. Hunter, Alexander Dow, J. Mill, and William Jones collected detailed information on Indian society. The English adaptation of casta to caste occurred in the early 17th century. It is crucial to note that caste was not identical to the indigenous concepts of jati, varna, or padabi, although these terms were often equated.

Concept of Jati, Varna, and Padabi

The concept of caste is often used interchangeably with the indigenous terms jati and varna. Hitesh Ranjan Sanyal suggested that while caste may be synonymous with jati to an extent, it is inappropriate for varna, which signifies a simpler social division. Varna originally referred to a colour-based classification and, as per the Manusamhita, denoted a division of labour: Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Sudras—with Brahmins occupying the highest position.

In contrast, jati denotes communities or clans tied by profession. A surname (padabi or title) acts as a suffix and indicates a person’s position in the social order. The attachment of social prestige or discrimination to a surname highlights its role as a social marker. These surnames, reflecting caste-based professions and roles, emerged from this structure. According to linguistic scholar S.K. Mukherji, epigraphic records are among the most reliable sources for tracing the origins of Bengali surnames. Bengal, a culturally and ethnically diverse region, experienced heightened diversification with the arrival of the Turks in the 13th century. Power dynamics were deeply rooted in jati, varna, and padabis.

Classification of Padabis

Bengali Brahmin Padabis: Brahmin surnames held social privilege due to their association with Vedic scholarship. These surnames often combined geographic and professional identifiers. Examples include:

• Bhattacharya: from ‘Bhatta’ (name) and ‘Acharya’ (teacher)

• Mukhopadhyay / Mukherjee: from ‘Mukhya’ (chief) and ‘Upadhyay’ (teacher)

• Bandopadhyay / Banerjee: linked to ‘Bandoghati’ (place of origin)

• Gangopadhyay / Ganguly: referencing proximity to the Ganges

Among Barendra Brahmins, common surnames include Bagchi, Lahiri, Maitra, Bhaduri, Sanyal, Ghoshal, and Kanungo.

Kayastha Padabis: Originally scribes and record-keepers, Kayasthas formed a distinct caste with many sub-divisions. Ashokan inscriptions refer them as ‘Rajukas’. Surnames like Dutta, Mitra, Ghosh, Guha, Basu, Deb, Chandra, Sen, Nandi, Dhar, and Bhadra have origins in administrative or religious roles.

Professional Guild-based Padabis: Many surnames emerged from manual and artisanal occupations, often considered impure. Examples include:

• Vaidyas/Baidyas (physicians): surnames like Gupta, Sen Gupta, Barat, Sen, Datta, Rakshit, Sircar

• Other occupations: Kumbhakar (potter), Sankhari (conch maker), Kansari (metalworker), Sunri (distiller), Napit (barber), etc.

Mercantile Community-based Padabis: The Baniks were prosperous but socially marginalised. Subarna Baniks, for example, settled in Saptagram and produced surnames like Seth and Basak. Brahmins reinforced purity taboos to uphold social stratification.

Titular/Hereditary Padabis: Conferred titles often became hereditary surnames. Examples include:

• Ray/Roy (king)

• Choudhury (superintendent)

• Sarkar, Mazumdar (landholders)

• RoyChoudhury, Chakraborty (overlord), Adhikari, Purkait

Outcaste/Ostracised Padabis: Interaction with Muslims led to the ostracisation of some Brahmin groups:

• Agradani Brahmins: degraded for accepting funeral gifts

• Pirali Brahmins: stigmatised due to ancestral conversion; notable descendants include the Tagore family of Jorasanko. Despite initial ostracism, their contributions transformed their social status.

These developments raise key questions: Did non-Brahmin and ostracised communities achieve social mobility in Bengal after the 18th century? If so, by what mechanisms?

Liberalist Ideologies and Western Education

By the late 19th century, the British aimed to classify and understand India through scientific and anthropological methods, influenced by liberal Western thinkers such as Adam Smith, James Mill, David Hume, Kant, Rousseau, and Bentham. Educational policies like Macaulay’s Minute (1835) and Wood’s Despatch (1854) introduced Western education to Indians.

This education facilitated social mobility and altered public perception of caste. A new, Western-educated class emerged—the ‘liminal class’—which embraced both traditional Indian and Western rational knowledge. English-language education enabled middle-class individuals from various castes to obtain clerical jobs, contributing to upward mobility.

Categories of the Liminal Class

According to the Oxford Dictionary, ‘liminal’ refers to something at the threshold or initial stage of a process, occupying a boundary position.

Social welfare activities:

• Pratap Chandra Ray, a Suta Aguri by caste, was honoured by the British for his social work.

• Raja Binoy Krishna Deb Bahadur, from the Suvarna Banik caste, rose through education and networking.

Commercial activities:

• By the 18th century, Subarna Baniks became central to Bengal’s commercial networks with European powers.

Educators and Reformers:

• Rai Kisto Das Pal Bahadoor and Rasik Krishna Mullick were Hindu College scholars.

• Girish Chunder Chowdhury, Sarat Chandra Ghosh Bahadoor, and Dr. Mahendra Lal Sarkar rose from Sadgop backgrounds.

• Nagendranath Basu, from a lower-middle-class Kayastha family, compiled the Bengali and Hindi Vishwakosh and became a respected editor and founder of Kayastha Sabha, challenging Brahminical dominance.

Bengali Print Media:

• The first Calcutta press emerged in 1777. Charles Wilkins and Panchanan Karmakar’s creation of Bangla metal type in 1778 revolutionised publishing.

• Initiatives like Digdarshan and newspapers such as Samachar Darpan, Tattwabodhini, and Samvad Purnochandradaya helped spread education and liberal ideas.

Conclusion

Earlier, social class was determined by caste and surname, with Brahmins and Kshatriyas at the apex. British liberalism and education, however, fostered a new, exclusive bhadrolok or liminal class in Bengal. This class, influenced by Western thought and judged on merit, intellect, and achievement rather than caste, included individuals from both high and low castes. This work explored how this diverse intelligentsia utilised surnames (padabis) to negotiate identity and achieve upward mobility in 19th-century Bengal.

Bibliography

Basu, Lokeswar. 1981. Amader Padabit Itihas. Calcutta: Ananda Publishers.

Bhattacharya, Jogendra Nath. 1896. Hindu Castes and Sects Calcutta: Thacker, Spink and Co.

Ray, Niharranjan. 1949. Bangalir Itihas: Adiparba (History of the Bengali People: Early Period). Kolikata: Dey’s Publishing.

Sanyal, Hitesh Ranjan. 1981. Social Mobility in Bengal. India: Papyrus.

Sur, Atul. 1988. Bharater Nrittatwik Parichay, Kolikata: Sahityalok.

Nandini Roy Choudhury lives in Abu Dhabi UAE. She is a classical musician and a M. Phil. research scholar in History. Worked as an efficient research assistant for professors and collaborators globally, she is actively teaching the musical nuances and basics of vocal training and vocal culture. She is also an active food, travel, lifestyle blogger, CEO at The Nomadic Flavours.

Nandini Roy Choudhury lives in Abu Dhabi UAE. She is a classical musician and a M. Phil. research scholar in History. Worked as an efficient research assistant for professors and collaborators globally, she is actively teaching the musical nuances and basics of vocal training and vocal culture. She is also an active food, travel, lifestyle blogger, CEO at The Nomadic Flavours.