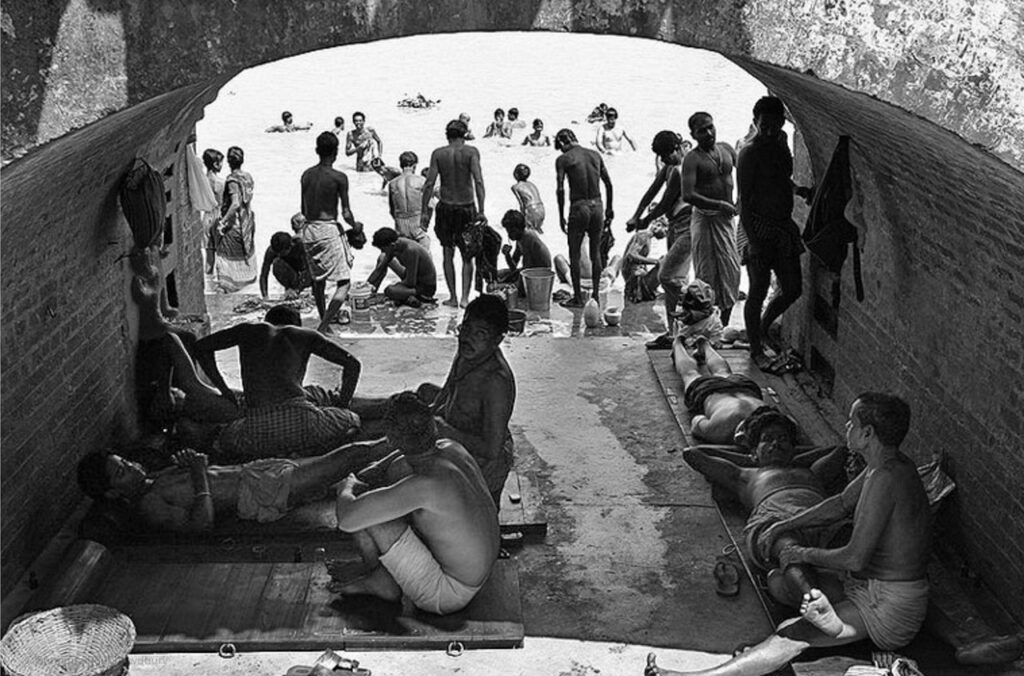

The ghats of Kolkata are an integral part of the city’s cultural, historical, and social life. Built along the eastern bank of the Hooghly River (a distributary of the Ganges), these riverfront steps and platforms serve multiple purposes: religious rituals, bathing, cremation, leisure, and even political and cultural gatherings. Kolkata’s ghats began to appear prominently during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a period when the city flourished under British rule as the capital of colonial India. Wealthy zamindars, merchants, and British authorities funded these ghats as acts of piety, philanthropy, or civic duty. Many ghats carry the names of their benefactors or associated families.

In the colonial era, ghats were not just for rituals—they became bustling nodes of commerce. Jetties near ghats facilitated cargo loading, ferry crossings, and passenger movement. The British administration also constructed public ghats for European residents, including changing rooms and waiting halls, blending European architectural styles with Indian functionality. Prinsep Ghat, built in 1841 in Greek Revival style, stands as a prime example of this cultural blend.

The ghats of Kolkata hold many rare and fascinating historical layers that enrich their cultural significance. The Armenian Ghat, built in 1734 by merchant Manvel Hazaar Maliyan, served as a vital hub for Armenian traders, with warehouses storing silk, indigo and opium. The Prinsep Ghat, constructed in 1841 by the British East India Company in honour of orientalist James Prinsep, functioned as a jetty for steamers and later became a favourite promenade for Europeans. Babu Ghat, commissioned in 1830 by zamindar Raj Chandra Das in memory of his wife, once boasted a grand colonial portico and was among the first to feature changing rooms for women—a progressive idea of its time. The Nimtala Ghat, one of the oldest cremation grounds, has long been sacred, with luminaries like Rabindranath Tagore cremated there, its name derived from the neem trees believed to purify the surroundings. The lesser-known Chandpal Ghat was once the ceremonial landing point for British Governors and Viceroys, marked by elaborate receptions and also served as a busy passenger and cargo jetty. Colonial observers such as Bishop Reginald Heber marvelled at the sight of hundreds bathing at sunrise, reflecting the bathing culture that later linked to public health campaigns. The tradition of Durga idol immersion, particularly at Bagbazar and Ahiritola, grew in the 19th century with the spread of community pujas, drawing massive public gatherings.

The ghats of Kolkata transformed into dynamic arenas of political discourse and nationalist mobilisation during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly in the struggle against colonial rule. In the wake of the Partition of Bengal in 1905, ghats such as Bagbazar, Ahiritola, and Chandpal became central to the Swadeshi Movement, hosting mass meetings that called for the boycott of British goods and the promotion of indigenous industries. Leaders like Surendranath Banerjee addressed vast crowds on the ghat steps, their speeches amplified by the openness of the riverfront. Alongside open agitation, the ghats also nurtured revolutionary secrecy. Groups like the Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar used these riverbanks for clandestine meetings, arms distribution, and planning sessions, their activities often disguised as casual gatherings. The proximity to the Hooghly offered both cover and escape routes by boat in case of police raids.

Among these spaces, Chandpal Ghat carried special symbolic weight, being the official landing point for British Governors and Viceroys. Nationalists frequently staged protests there, handing out pamphlets and organising demonstrations to confront imperial authority at its very doorstep. At the same time, cultural nationalism found expression on ghat platforms through Swadeshi melas, public readings, processions, and Durga idol immersions that blended religious fervour with political slogans. These open-air gatherings were strategic: they had no entry barriers, were accessible via ferries and trams, and were highly visible to British officials travelling on the river. Notable figures such as Chittaranjan Das, Bipin Chandra Pal, and even Rabindranath Tagore were associated with such events, reinforcing the ghats as spaces of shared resistance.

The momentum carried into the Gandhian era, when ghats became sites of burning foreign goods, pledge ceremonies for boycotts, and symbolic acts of defiance during the Salt Law protests. The choice of the riverside was deliberate, for the Hooghly River, an extension of the sacred Ganges, embodied purity, renewal, and freedom. By situating their struggles along its banks, nationalists linked political resistance to spiritual symbolism, ensuring that the ghats of Kolkata were etched not only into the city’s cultural history but also into the collective memory of India’s freedom movement.

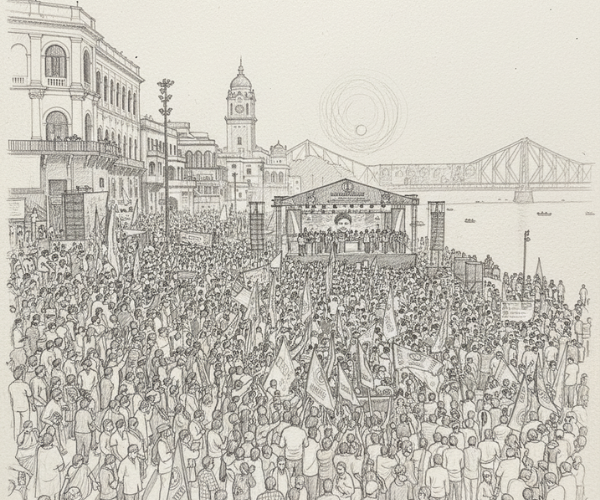

The ghats of Kolkata, once central to anti-colonial mobilisation, continued to serve as vibrant spaces of political and social discourse in the decades following Independence. In the post-1947 era, their role shifted from freedom struggle to mass gatherings, rallies, and cultural activism. Bagbazar and Ahiritola ghats, long associated with public life, became meeting points for leftist organisations and trade unions, particularly during the rise of communist politics in Bengal. The Communist Party of India and later the CPI(M) often addressed workers, boatmen, and local residents from these open-air platforms. Chandpal Ghat, once a ceremonial landing site for colonial governors, was redefined as a people’s space, hosting demonstrations against government policies in the 1950s and 60s.

By the 1970s, the Naxalite movement transformed many ghats into secret rendezvous points for radical youth. North Kolkata ghats like Bagbazar and Kumartuli offered both concealment and quick escape routes via the river during police crackdowns, while graffiti near these spaces signalled resistance and propaganda. As militant politics receded in the 1980s and 1990s, the ghats saw a different wave of cultural politics. Prinsep Ghat and others became sites for book fairs, poetry readings, street theatre, and heritage-driven rallies, where cultural expression carried sharp political undertones. Environmental protests also began to emerge, with citizens voicing concern about pollution and encroachment of the Hooghly.

In the 2000s, state-led beautification projects under Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee transformed several ghats into tourist attractions. While this revival enhanced their heritage appeal, it also sparked debates about gentrification and displacement of marginalised communities along the riverbank. Simultaneously, public interest litigations and demonstrations for ecological conservation brought civic activism to these spaces.

The contemporary era (2010–present) has further diversified the political and cultural role of ghats. Under the Trinamool Congress government, they have been appropriated as venues for state-sponsored events, cultural festivals, and ritual celebrations like Chhath Puja, while also serving as backdrops for political imagery. Prinsep Ghat and Millennium Park have become stages for youth movements, candlelight vigils, and protests on gender violence, most notably after the Nirbhaya case. Environmental groups and river conservation campaigns regularly use ghats as platforms to raise awareness, often blending grassroots activism with social media visibility.

Today, ghats remain deeply embedded in political symbolism. During elections, parties ranging from TMC to BJP and CPI(M) use these spaces for rallies, processions, and religious-cultural optics. Bagbazar Ghat during Durga idol immersion becomes a political spectacle where leaders mingle with citizens, while Prinsep Ghat’s redeveloped promenade frequently features in campaign advertisements as proof of ‘development’.

Across these decades, several themes stand out: the transformation of ghats from anti-colonial platforms to symbols of cultural heritage and urban progress; the intersection of religion and politics where immersion ceremonies double as populist displays; and the reclaiming of ghats by activists—environmentalists, feminists, and youth movements—who continue to shape them as spaces of protest, resistance, and democratic engagement in modern Kolkata.

Photo Courtesy : Sumanta Roy Chowdhury

What a detailed description of every bit of life of the people, their ritualistic approach, their hindrances, their protests, their struggle to survive,. Kudos.. 👏🏼👏🏼🙏🏼😇👌🏼👌🏼

Сбор качественных хрумер ссылки https://www.olx.ua/d/uk/obyavlenie/progon-hrumerom-dr-50-po-ahrefs-uvelichu-reyting-domena-IDXnHrG.html помогает повысить видимость сайта и улучшить его позиции в поиске.

wonderfull content