From Mrinmoyee To Chinmoyee

The celebration of Durga’s victory over the demon Mahishasura is rooted in ancient Hindu texts like the Devi Mahatmya, part of the Markandeya Purana (approximately 400–600 CE), which narrates the story of the goddess’s battle with Mahishasura and forms the basis of Durga’s worship. The timing of the Durga Puja in autumn, known as Akal Bodhan (untimely invocation), is attributed to Lord Rama, who is believed to have sought Durga’s blessings during this period in his battle against Ravana, breaking with the tradition of her springtime worship. The first recorded Durga Puja in Bengal is believed to have been organised by the aristocratic Sabarna Roy Choudhury family, who held significant political and economic power. In 1606, Lakshmikanta Gangopadhyay, an ancestor of the family, initiated Durga Puja as an act of devotion, and over time, it became an annual event celebrated by the family and the surrounding community.

The Barisha Durga Puja is unique because it is celebrated by different branches of the Sabarna Roy Choudhury family, with several households within the family conducting their own version of the puja.

Following age-old rituals, many of which have remained unchanged for over 400 years, currently, there are seven pujas conducted by various branches of the family, all of which trace their origins back to the original puja, established in 1606. During the rule of the British East India Company in the eighteenth century, wealthy zamindars and merchants, especially in Kolkata, started hosting Durga Puja to display their wealth and power. Notable families like the Raja Nabakrishna Deb of Shobhabazar, in 1757, played a significant role in elevating the grandeur of Durga Puja. His celebrations after the British victory in the Battle of Plassey (1757) were marked by opulence, inviting British officials to witness the festival.

According to Nair, Shobhabazar Rajbari family owning its ancestry to Nabakrishna came to be associated with the neighbourhood after they were displaced in 1758 from their settlement in Gobindapur which was being cleared to include the maidan (a huge green meadow) and the fortification of the Fort William. The Deb family was compensated by the Fort William Council, enabling them to purchase land in Pataldanga. Though there is no clarity of the Deb’s residence in Pataldanga, but when Nabakrishna became the head of the family, they eventually moved to Shobhabazar, where land could be purchased at relatively low prices. It was only in the early nineteenth century, Baroyari Puja (public or community Durga Puja) emerged. The first public Durga Puja is credited to a group of twelve friends from Guptipara in Hooghly district around 1790, who pooled their resources together to celebrate the festival. This eventually gave rise to what is now known as Sarbojanin Durga Puja, where people from all backgrounds contribute to the celebrations. This transformed the festival from a private, family-centered event to a public, community-wide one. By the twentieth century, particularly during the Bengal Renaissance and the rise of nationalism in British India, Durga Puja took on a more egalitarian and community-oriented spirit. It became a platform for social and political expressions of unity, especially during the freedom movement.

Kumartuli: The Artisans’ Heart of Durga Puja

The word Mrinmoyee comes from the Sanskrit word mrina, meaning earth or clay. Durga’s mrinmoyee roop refers to her physical, clay form, which is created by artisans (often in areas like Kumartuli in Kolkata) for the Durga Puja festival. As Durga Puja became popular in the eighteenth century, and the demand for idols grew, the kumors (potters) settled in a colony near Shobhabazar, near the banks of the Hooghly River at the northern fringes of Kolkata. Nestled along the banks of the Hooghly River, Kumartuli is a vibrant neighborhood in North Kolkata, renowned for its centuries-old tradition of idol-making.

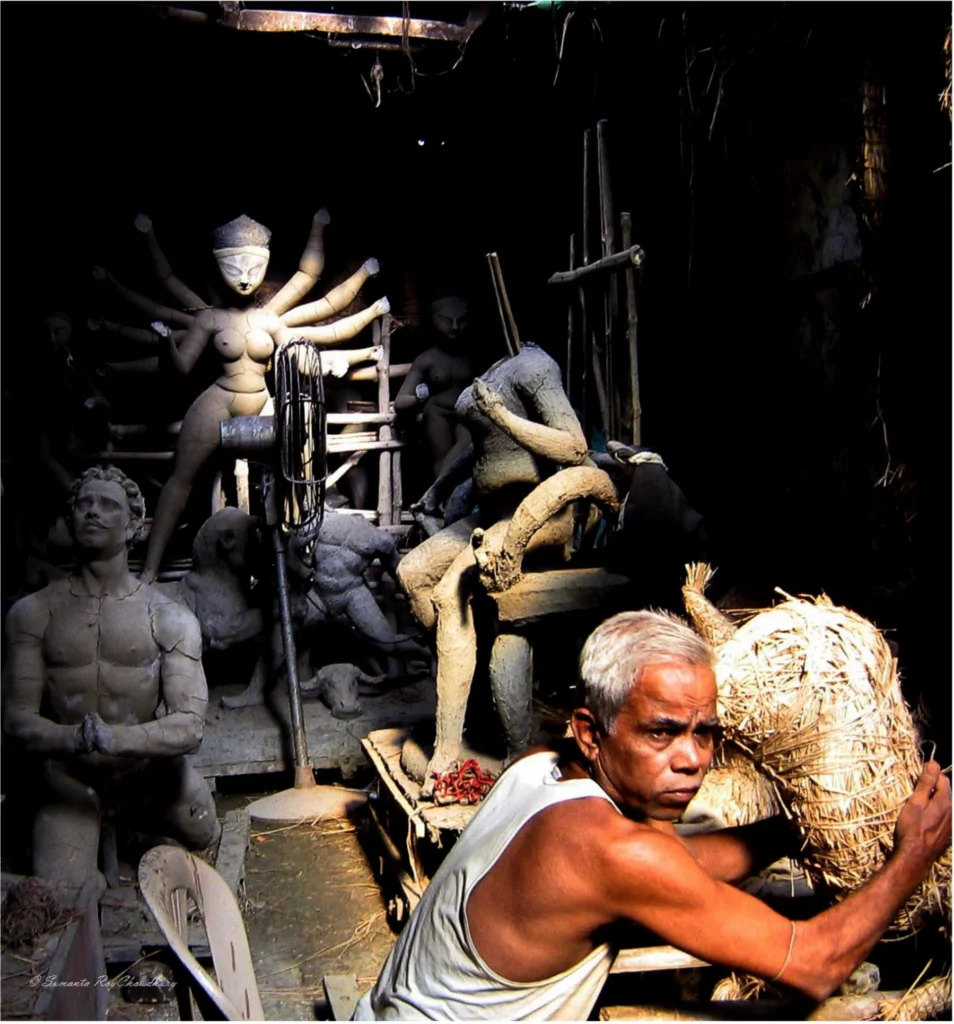

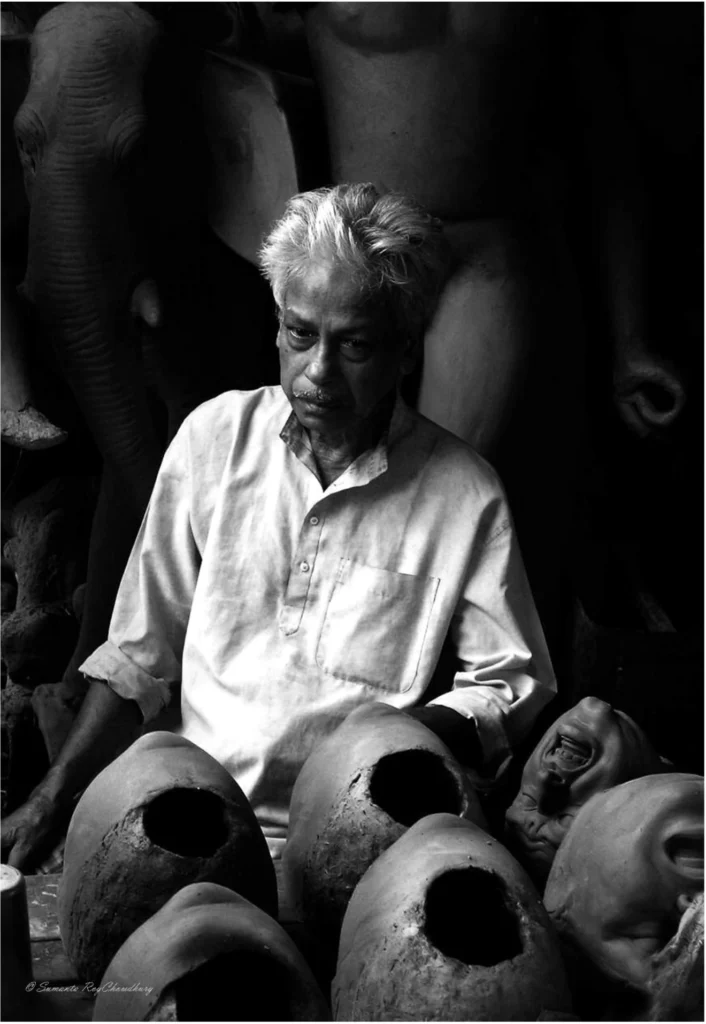

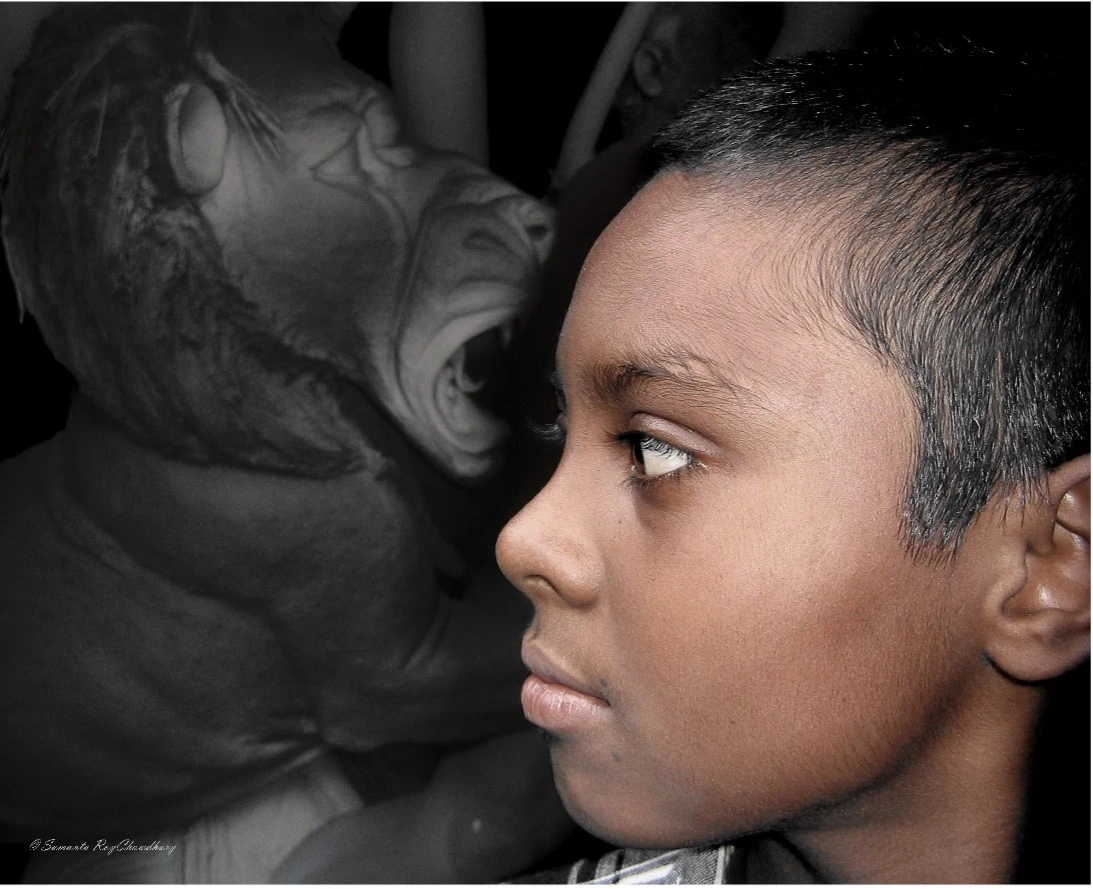

For months before the festival, the narrow labyrinth of lanes in Kumartuli transforms into a buzzing workshop where master artisans shape lifeless clay into stunning representations of Goddess Durga and her divine entourage. Using simple materials—straw, bamboo, and clay from the Ganges—these artists imbue their creations with intricate details and expressions that evoke awe and reverence. Each idol is a work of art, embodying the essence of the divine while reflecting the regional and individual styles of the artisans. Kumartuli’s connection with Durga Puja goes beyond the physical creation of the idols. It’s a symbol of continuity, carrying forward traditions that have evolved since the eighteenth century. The artisans meticulously work through the various stages of idol-making, starting from collecting clay for the idol, which is brought from Uluberia, situated in the Howrah District along the banks of the Hooghly. However, the bank of the river is not the only place from which clay is used in making the idols of Goddess Durga. As per Hindu tradition, when the idol of Goddess Durga is prepared, four things are very important—mud from the banks of the Ganga, cow dung, cow urine and punya mati or soil from outside brothels, known as Nishiddho Pallis, without which the idol is considered incomplete. From erecting the framework, applying the final coat of vibrant paint and adornments, till adding the final touch to the idol’s eyes, known as chokkhu daan—each step symbolises the act of creation itself. For the artisans of Kumartuli, the idols are not just their craft but a manifestation of their devotion and legacy, passed down through generations. During Durga Puja, these creations stand at the heart of pandals—elaborate temporary structures where the community gathers to celebrate. Kumartuli’s significance extends far beyond Kolkata, with its idols being shipped across the globe to Bengali communities that celebrate the festival in countries like the UK, the USA and Australia. The rhythmic sound of dhaak (drums), the fragrance of incense, and the vibrant colours of the idols from Kumartuli all converge during the five-day celebration, uniting artistry, devotion, and community in a magnificent symphony.

Through the skilled hands of Kumartuli’s artisans, the festival of Durga Puja comes alive year after year, keeping traditions alive while allowing space for new interpretations and expressions of faith.

A Festival For All

One of the most inclusive and community-driven festivals in India, Durga Puja transcends economic boundaries and unites people from all walks of life. Often held in elaborate pandals, Sarbojonin pujas are funded through donations from local residents and businesses. Being a collective effort, every neighbourhood or community has its own celebrations that are accessible to all. Pandals are open to everyone, and people from different economic backgrounds freely visit and participate in the festivities.

As the embodiment of Shakti (divine feminine power), Goddess Durga symbolises empowerment and strength. This resonates deeply with women, who often lead puja-related activities such as organising rituals, preparing bhog, and leading sindoor khela. The Kumari puja was initiated by Swami Vivekananda to celebrate and recognise feminine power. While traditionally, Durga Puja rituals were led by male priests, in recent years, several female priests have broken this norm, symbolising a shift towards gender inclusivity. A closer look into the inclusive nature of the festival reveals that many of the idol-makers in Kumartuli belong to lower economic backgrounds or to different religions. Transcending religious and cultural boundaries, their craftsmanship is celebrated and showcased worldwide.

Efforts to include people with disabilities have grown in recent years, with several organisations and communities taking steps to make pandals more accessible and welcoming. Many prominent pandals have begun installing ramps, wheelchair access and sign language interpreters to ensure that people with physical disabilities can participate in the festivities.

Special Durga Puja celebrations have been organised for children with autism, where they participate in rituals, cultural performances, and even idol-making. Some pandals have welcomed the participation of queer individuals in rituals and cultural activities, recognising their role in society and challenging traditional gender norms. The representation of LGBTQ+ community in cultural performances and other Durga Puja-related events, have promoted greater visibility and acceptance. While there is always room for further inclusivity, particularly in terms of accessibility and representation, the festival continues to evolve in ways that embrace and celebrate diversity.

Durga’s mrinmoyee roop symbolises her earthly, clay form, through which she is worshipped in the physical world. This form transforms into her chinmoyee roop, representing her eternal, formless essence—pure consciousness and divinity. The journey from mrinmoyee to chinmoyee is a profound reminder of the interconnectedness of the material and spiritual worlds and the impermanence of physical forms in contrast to the eternal divine spirit.

The ten arms of Goddess Durga symbolise that she protects her devotees from all directions, the eight corners and from sky and earth. Here’s what each weapon symbolises:

Trishul, received from Lord Shiva, its three edges denote the three qualities of humans—tamas (inactivity and lethargic tendencies), rajas (hyperactivity and desire) and sattva (positivity and purity). Conch, gifted by Lord Varun, symbolises the primordial sound called Aum from which the entire creation emerged.

Chakra, revolving around Durga’s fingers and received from Vishnu, it shows that she is the center of creation and all the universe revolves around her.

Lotus, gifted by Brahma, stands for the awakening of spiritual consciousness in a soul.

Kharga, received from Brahma, implies the sharpness of intellect enjoining humans to use the sense of discrimination to overcome negativity.

Bow and arrow, given by Vayu and Surya, are the symbols of energy.

Gada, received from Kubera represents strength, power and authority, necessary to destroy evil. It reminds devotees to surrender their ego and pride before the divine.

Bajro, presented by Indra, denotes firmness of spirit.

Snake, given by Shiva, symbolises transcendence from the lower state of consciousness to the higher state of existence, experiencing pure bliss.

Axe, received from Vishwakarma, symbolises the destruction of evil and ignorance, severing attachments, power and authority, discipline and physical strength. It reinforces her role as a protector and a fierce warrior who fights for dharma (righteousness) and the welfare of her devotees.

We are grateful to Sumanta Roy Chowdhury for the visuals he has kindly shared with us.

Two works that have helped us in shaping the narrative are Raj Sekhar Basu,‘Nabakrishna Deb of Sovabazar 2’, https://www.academia.edu/86683430/Nabakrishna_Deb_of_Sovabazar_2 (accessed on 1 October) and Sumanta Roy Chowdhury, (ed), Coomertolly: Clayfield of God (Kolkata: Sparsha, 2008).

Readers might like to listen to this song, which has inspired the title of the narrative; composed by Kazi Nazrul Islam, sung by Arijit Chakraborty: