SUBARNA BANERJEE

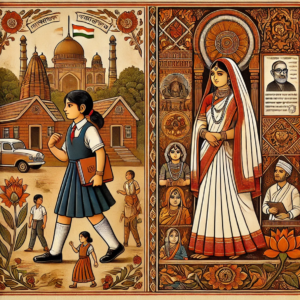

Bengal has long been a land of reformers: from Raja Ram Mohan Roy, who fought against sati and championed women’s education, to Rabindranath Tagore, who envisioned a society where women could walk free; from Kazi Nazrul Islam, whose poetry thundered against oppression, to Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, who imagined a world where women led the way. The Bengal Renaissance also saw the rise of women writers like Swarnakumari Devi and Toru Dutt, who dared to carve their own space in literature. Yet, for all its intellectual progressivism, Bengal remains trapped in a paradox. It has one of the highest rates of child marriage in India, where many young girls still see their education cut short by tradition and poverty. This has grievous implications, leading to early pregnancies and endangering both child and maternal health.

Bengal has long been a land of reformers: from Raja Ram Mohan Roy, who fought against sati and championed women’s education, to Rabindranath Tagore, who envisioned a society where women could walk free; from Kazi Nazrul Islam, whose poetry thundered against oppression, to Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, who imagined a world where women led the way. The Bengal Renaissance also saw the rise of women writers like Swarnakumari Devi and Toru Dutt, who dared to carve their own space in literature. Yet, for all its intellectual progressivism, Bengal remains trapped in a paradox. It has one of the highest rates of child marriage in India, where many young girls still see their education cut short by tradition and poverty. This has grievous implications, leading to early pregnancies and endangering both child and maternal health.

In response to this persistent challenge, the West Bengal government launched Kanyashree Prakalpa in 2013, a programme designed to delay marriage by keeping girls in school. A decade later, the scheme has changed lives, but questions remain: has it gone far enough?

At its core, the programme was simple: give financial incentives to girls to stay in school and delay marriage. The scheme is two-tiered. The first component is the K1 grant, an annual scholarship of ₹1000, for every year a girl remains in school.

The second component, the K2 grant, is a lumpsum payment of ₹25000 given to a girl upon reaching the age of 18, pursuing education, and remaining unmarried. Over a decade later, the programme has reached over 80 lakh girls and significantly reduced the number of underage marriages in the state. Kanyashree is unlike many other conditional cash transfers (CCT) programmes in India. While most schemes offer financial support to families, Kanyashree makes the girl herself the direct beneficiary. This isn’t just about money; it’s about shifting mindsets. When a young girl in a rural village receives a bank deposit in her name, it sends a message: You matter. Your education matters. By starting early, at the age of 13, Kanyashree attempts to shape aspirations, reinforcing that school is more than just a waiting period before marriage.

The impact has been visible. School enrollment among girls has increased, and more young women are completing secondary education. But the successes stop short of transforming the classroom experience. While more girls are going to school, attendance rates haven’t changed much, nor have learning outcomes. Schools have not necessarily improved in quality, and many students still struggle with foundational skills. This is a familiar problem across India. Education is expanding, but without real improvements in teaching and infrastructure, it risks becoming a hollow achievement.

But Kanyashree’s impact extends beyond textbooks. Studies show that the programme has improved young women’s mobility. Beneficiaries are more likely to travel outside their homes alone, a small but significant shift in a society where freedom of movement is often gendered. The programme’s requirement that beneficiaries have a bank account has also fostered financial literacy, making young women more comfortable handling money, an essential step towards economic independence. Perhaps most importantly, evidence suggests that Kanyashree girls are less likely to tolerate intimate partner violence. Education, even when imperfect, has given them the confidence to question harmful norms and demand better for themselves.

Still, challenges remain. In some families, the financial incentive of Kanyashree has backfired. Parents, seeing the grant as a short-term benefit, still push their daughters into marriage as soon as they turn 18. Boys, meanwhile, have been left out of the conversation, leading to unintended resentment in communities where girls are receiving government support while boys struggle with uncertain futures. If Kanyashree is to be truly transformative, it needs to be accompanied by policies that address gender disparities as a whole.

Kanyashree has not been immune to inefficiencies and leakages. Reports suggest delays in disbursing financial assistance, especially for the one-time K2 grant of ₹25,000, which often reaches beneficiaries late, sometimes well past the intended school-leaving age. There have also been cases of ineligible beneficiaries receiving funds due to weak verification mechanisms, as well as concerns that some families continue to marry off their daughters early despite receiving the stipend.

Since its inception, the state has spent over ₹12,000 crore on the programme, amounting to roughly 0.1-0.2 % of the state’s gross domestic product annually. While substantial, this is still lower than allocations for other welfare schemes like Swasthya Sathi or Lakshmir Bhandar. Furthermore, compared to overall education spending, Kanyashree is a niche intervention, accounting for about 3% of the state’s total education budget annually.

West Bengal has always been a state of contradictions: home to some of India’s most progressive ideas, yet weighed down by entrenched social realities. Kanyashree represents an important step in bridging this gap, but it cannot be the final step. The next phase of empowerment must focus on what happens after school – on employment, vocational training, and creating real opportunities for women to use their education. Otherwise, we risk raising a generation of educated young women with nowhere to go.

Kanyashree’s success is not just in the numbers but in the stories of the girls who, for the first time, see a different future for themselves. But if Bengal truly wants to honour the legacy of its reformers, the work cannot stop here. The fight for women’s empowerment is not just about staying in school – it’s about what comes next.

Bibliography

Banerjee, S., & Sen, G. (2024). Persistent effects of a conditional cash transfer: A case of empowering women through Kanyashree in India. Journal of Population Economics, 37(66), https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-024-01045-4

Dey, S., & Ghosal, T. (2021). Can conditional cash transfer defer child marriage? Impact of Kanyashree Prakalpa in West Bengal, India. Warwick Economics Research Papers (No. 1333). University of Warwick. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/p/wrk/warwec/1333.html

Government of West Bengal. (2024). Budget Publication No. 30. Finance Department. Retrieved from https://finance.wb.gov.in/writereaddata/Budget_Publication/2024_bp30.pdf

Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. (n.d.). State-wise gross state domestic product (GSDP) growth rates at constant prices (Base year 2011-12). Government of India. Retrieved from https://www.mospi.gov.in/state-wise-gross-state-domestic-product-gsdp-growth-rates-constant-prices-base-year-2011-12

Sen, G., & Thamarapani, D. (2023). Keeping girls in schools longer: The Kanyashree approach in India. Feminist Economics, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2023.2263542

UNICEF India. (2024, October 17). Kanyashree Prakalpa: Building a brighter future for every girl in West Bengal. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/india/stories/kanyashree-prakalpa-building-brighter-future-every-girl-west-bengal-0

Subarna Banerjee is a PhD candidate at Shiv Nadar University. She is interested in empirical work in Gender, Political Economy, and Education.