SANDIPAN DEB

Satyajit Ray was born on May 2, 1921 to a family of extraordinary talent. His grandfather, Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury was a legendary children’s author, painter and musician. Upendrakishore’s eldest brother Saradaranjan Ray was an eminent academician and was known as “W.G. Grace of Bengal” for his role in popularising cricket in the province (and his WG-esque flowing beard). Younger brother Kuladaranjan was the first to translate Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Jules Verne into Bengali.

Satyajit Ray’s father, Sukumar Ray, was arguably the greatest Bengali children’s author, his whimsical and fantastical poems and tales remaining unparalleled in Indian literature. Many of Satyajit’s aunts and female cousins were also literary luminaries. Together, Upendrakishore, Sukumar, and Satyajit Ray rank among the best-selling Bengali children’s authors of all time. Nearly every Bengali child who learns to read first encounters Upendrakishore’s fairy tales, then moves on to Sukumar’s playful verses, and finally delves into Satyajit’s stories of the eerie and supernatural, the quiet dignity of the meek, and the adventures of detective Feluda and scientist Professor Shonku.

Sukumar passed away when he was only 35, with Satyajit two years old. The young Satyajit—or Manik (gem)—seems to have been a solitary child, though adored by his uncles, aunts and elder cousins. One rarely acknowledged aspect of Satyajit Ray’s storytelling—whether in print or film—is that every child he portrays is an only child, never with siblings. Each of these characters possesses a sharp curiosity and a vivid imagination, likely reflecting Satyajit Ray’s own childhood experiences.

When he was seven, Manik travelled with his mother to Shantiniketan and met Rabindranath Tagore, a close friend of both his grandfather and father. In the boy’s autograph book, Tagore wrote an eight-line poem—now quite familiar to Bengalis, though few may be aware of the Satyajit connection. “Let him keep this. When he’s a little older, he’ll understand it,” Tagore told Manik’s mother. The poem says Tagore had travelled the world at great expense and seen every country, the greatest mountains and the vastest oceans, but he had failed to see the world outside his own door: a single drop of dew on a stalk of rice—“a drop that reflects in its convexity the whole universe around it,” as Ray later commented. This idea became the core of Ray’s cinematic vision—discovering the universal in the simplest objects, gestures, or the interplay of light and shadow.

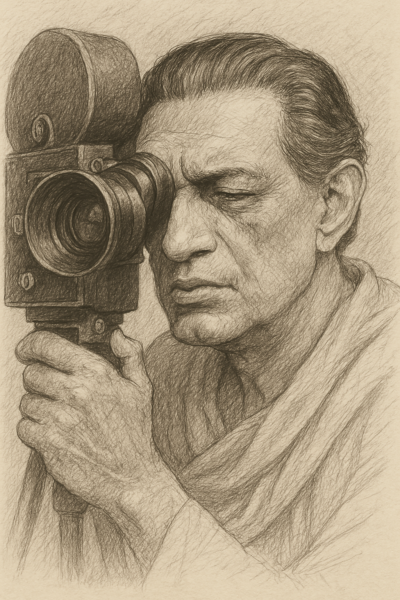

“The raw material of cinema is life itself”

Ray shared with his biographer, Marie Seton (Portrait of a Director), that as a child, he would spend hours exploring the mysteries of light. “There was an intriguing hole in the street door of his uncle’s house. Manik would stand in front of this with a piece of broken frosted glass in his hand to catch the reflection of people moving outside on the street. The shaft of light coming through the hole worked like a box camera. Years later, he told his photographer friend A. Huq that the images impressed him more when there were sounds with the images. Thus, he was dimly aware of audio-visual effects at a very early age.”

Sukumar had hoped his son would study at Tagore’s university. However, by his own admission, Satyajit grew up immersed in light English fiction, with little interest in Indian art and literature. Yet, after graduating from college, he honoured his mother’s wishes and joined Kala Bhavan in Shantiniketan for a four-year art course. However, after two and a half years, he discontinued because he “just felt that I had learnt all that was there to learn”, but his time at Shantiniketan and class trips to the great art centres of India like Ajanta, Ellora and Konark would have a deep influence on him. “At last I was beginning to find myself and my roots.”

“What is wrong with Indian films?” is the title of Ray’s first published article on cinema, in The Statesman in 1948. “The raw material of cinema is life itself,” he wrote. “It is incredible that a country that has inspired so much painting and music and poetry should fail to move the filmmaker. He has only to keep his eyes open, and his ears. Let him do so.” Two years later, in London, Bicycle Thieves, which he watched more than a dozen times, would be a revelation: cinema had the power to capture life in all its depth and dignity, transform fleeting moments into something eternal, and uncover profound truths in seemingly insignificant details—all without being constrained by budgets or the sophistication of equipment.

Bicycle Thieves seemed to validate what he had been thinking and what he had gleaned from Renoir. Through his filmmaking career, Ray would adhere to some tenets that he had learnt from Renoir. For instance, “You don’t have to have too many elements in a film, but whatever you do, must be the right elements, the expressive elements.” And “one quality to be found in a great work of cinema is the revelation of large truths through small details.” (This is an echo of Tagore’s little poem.)

All this also heightened Ray’s frustration with Indian films. In a March 1952 article, he wrote: “In the 30 years of its existence, the Bengali film on a whole has not progressed one step towards maturity.… There is no director in Bengal whose work even momentarily suggests a total grasp of the film medium in its dramatic, plastic and literary aspects.”

Things were about to change. Ray had written the screenplay of Pather Panchali (The Song of the Road, 1955), which would be his first film, on the ship home from Britain two years ago.

“In the beginning there was…Pather Panchali”

It is difficult to imagine today how revolutionary Pather Panchali was as an Indian film. Wrote Sham Lal, legendary editor of The Times of India, in his paper (under the pen-name Adib), after watching it in a morning show in Bombay: “It is absurd to compare it with any other Indian picture—for even the best of the pictures produced so far have been cluttered with clichés. Pather Panchali is pure cinema.… (Ray) composes his shots with a virtuosity he shares with only a few directors in the entire history of cinema… The secret of his power lies in the facility with which he penetrates beneath the skin of his characters, and fixes what is in their mind and in their hearts—in the look of the eyes, the trembling of the fingers, the shadows that descend on their faces.”

For director Adoor Gopalakrishnan, writing in 1998, “(Pather Panchali marked) the beginning of the true Indian cinema—a beginning for all of us. It was not only a total negation of the soulless and superficial all-India cinema indifferent to real people and issues, but also an affirmation of the emergence of the first consummate artist on the subcontinent’s motion picture scene. So, for all of us…in the beginning there was…Pather Panchali.”

The film was contracted to run for six weeks in a Calcutta theatre chain. It was taken off when the contractual period ended, even though it was running to full houses, because the chain had been booked months ago to release renowned South Indian producer-director S.S. Vasan’s Insaaniyat, starring Dilip Kumar and Dev Anand. The day after Pather Panchali was taken off, Ray was woken up by an early-morning visitor. It was Vasan. Vasan told Ray that he had watched Pather Panchali the night before and “If I had known that this was the film Insaaniyat was going to replace, I would have certainly withheld its release. You have made a great film, sir.”

It might seem surprising that Martin Scorsese—whose style and subject matter appear vastly different from Ray’s—championed the campaign for Ray’s honorary Oscar, which he received in 1992. But was it really so unexpected? Scorsese later recalled: “I was 18 or 19 years old (when I watched Pather Panchali for the first time) and had grown up in a very parochial society of Italian-Americans, and yet I was deeply moved by what Ray showed of people so far from my experience. I was moved by how their society and their way of life echoed the same chords in all of us.” And it can be argued that Scorcese’s “uncharacteristic” films like The Age of Innocence and Hugo carry Ray’s influence, with access to a level of funds and technology that Ray could not have dreamed of.

From Apu to Ashim to Somnath

“My films are all concerned with the new versus the old,” Ray once explained. Ray’s films can also be seen as a chronicle of Bengal—and India—captured through meticulously composed snapshots. Jalsaghar (The Music Room, 1958) portrays the decline of the feudal order, as a cash-strapped zamindar hosts one final grand musical soirée in a desperate bid to assert his superiority over a wealthy upstart. Devi (The Goddess, 1960) delivers a scathing critique of religious superstition, as a zamindar’s prophetic dream convinces him that his daughter-in-law is the incarnation of Durga, leading to tragic consequences.

In Kanchenjungha (1962), an arrogant brown sahib faces a humbling realisation—his influence no longer holds sway in a newly awakened India. Mahanagar (The Big City, 1963) explores the emergence of the modern Indian woman, as Arati steps into the role of breadwinner after her husband loses his job. Ashani Sanket (Distant Thunder, 1973), set against the backdrop of the Bengal Famine of 1943, examines how rigid social structures—such as caste—begin to crumble in the face of widespread hunger.

Apu, born in a small village in an indigent Brahmin family, is tied down by economic and social circumstances, which however cannot tether his mind or spirit. In Pather Panchali, he is the curious child soaking in the life around him—a life stained by tragedies over which no one has any control. In Aparajito (The Unvanquished, 1956), his ambition to be a part of the wider world collides with his mother’s desire and need to keep her beloved son close to her—an issue that teenagers have faced across the world and from time immemorial.

In the final film of the trilogy, Apur Sansar (The World of Apu, 1959), we see the achingly beautiful love story of Apu and his wife Aparna, are devastated at Aparna’s death in childbirth, and want to cheer with abandon when Apu, who had spent years blaming his son Kajal for Aparna’s death, walks into the sunset (technically, sunrise) with little Kajal on his shoulders. As a work of pure humane communication that rises above linguistic, racial, geographical barriers, the Apu trilogy is unlikely to be surpassed.

But do the young men in the films Ray made in the 1970s on contemporary themes—after long being accused of “living in an ivory tower”—represent Apu-figures in a different time and context?

In Pratidwandi (The Adversary, 1970), the sensitive and imaginative Siddhartha—much like Apu before him—struggles to find a job, feeling increasingly powerless in a world torn between clashing ideologies and shifting values. Ashim in the underrated Aranyer Dinratri (Days and Nights in the Forest, 1970) and Shyamalendu in Seemabaddha (Company Limited, 1971) represent what Siddhartha might have become had he chosen to suppress his voice in job interviews. Both are successful executives, yet Ashim questions whether every step up the corporate ladder is, in fact, a step down in morality, while Shyamalendu willingly sacrifices his principles in the ruthless pursuit of a boardroom seat.

The most morally compromised of them all is Somnath in Jana Aranya (The Middleman, 1975). Unable to secure employment, he descends into the murky world of “order supply,” where business deals come with unspeakable ethical compromises. To win a lucrative contract, he must provide the decision-maker with a woman—and ultimately, he delivers his best friend’s sister to a businessman’s hotel room. The Middleman was released at the peak of Indira Gandhi’s Emergency, a time when the dreams of independent India lay in ruins. Somnath’s father, once a believer in those dreams, stands as a confused, tragic relic of a lost era.

With The Middleman, Ray entered a darker phase of filmmaking that would persist until the end of his career. Until this point, his films were marked by their refusal to pass moral judgement. His famous remark, “Villains bore me,” reflected his nuanced storytelling. As Amartya Sen observed, “In Ray’s films, villains are remarkably rare, almost absent. When terrible things happen, there may be nobody clearly responsible. And even when someone is clearly responsible—like Dayamoyee’s father-in-law in Devi, who drives her to despair and ultimately suicide—he too is a victim, not entirely devoid of humanity… Ray chooses to convey the complexity of social situations that make such tragedies inevitable, rather than offering easy explanations rooted in greed, cruelty, or villainy.”

Yet, over time, this empathetic humanism would fade from Ray’s cinema.

Charu, Arati, Aparna

Satyajit Ray believed that women were more intelligent than men. In The Inner Eye, he told biographer Andrew Robinson that because women were physically weaker, they developed sharper intelligence and heightened perceptual abilities. This belief is reflected in the rare sensitivity with which Ray portrayed women in his films.

Charulata (1964) was Ray’s personal favourite among all his works. Madhabi Mukherjee delivers a brilliant performance as Charu, but it is Ray’s camera that elevates her presence, capturing the subtlest shifts in her thoughts and emotions. Every flicker of expression on her face is illuminated, making it impossible for men—not just within the film but also the audience—to resist falling in love with her.

Karuna in Kapurush (The Coward, 1965) is far more resolute than her lover Amitabha, the so-called coward of the title. In Nayak (The Hero, 1966) and Seemabaddha (Company Limited, 1971), the women played by Sharmila Tagore embody honesty and unshakable values, serving as the moral compass in a world of compromises. However, Ray’s two most compelling female characters are Arati in Mahanagar (The Big City, 1963) and Aparna in Aranyer Dinratri (Days and Nights in the Forest, 1970).

Arati is thrust into the working world out of necessity, taking up a job as a door-to-door salesperson. Initially hesitant, she gradually finds her footing, emerging as the anchor of her family. Her quiet strength is best exemplified when she resigns in protest against the racially motivated mistreatment of an Anglo-Indian colleague. A tribute to the resilience of women, Mahanagar is undoubtedly one of Ray’s finest films.

If Arati represents feminine strength, Aparna embodies the enigma of femininity. “I can’t figure you out,” Ashim tells her. “Is that necessary?” she replies. Later, she confesses, “When I first saw you, I thought it would be fun to shake your confidence.” “You have,” he admits. Their conversation deepens: “You haven’t known real sorrow, have you?” Aparna asks. She, on the other hand, has witnessed her mother’s death in a fire and endured her brother’s suicide. Despite Ashim’s material success, it is Aparna who is the more grounded, insightful, and compassionate of the two. By the film’s end, Ashim has fallen deeply in love with her, but she offers him no promises. Accustomed to always getting what he wants, he must now grow to be worthy of her.

The Retreat from Humanism

So how does one really evaluate Satyajit Ray? Perhaps Pauline Kael, arguably the finest film critic of the 20th century, said it for all of us: “Ray’s films can give rise to a more complex feeling of happiness in me than the work of any other director.” That is infinitely more than most artists can achieve, or even hope to achieve. That, in itself, is enough.

Sandipan Deb, former Managing Editor of Outlook, was Editor of Financial Express, and Founder-Editor of Open and Outlook Money magazines.

A version of this article was published in Outlook magazine in May 2021 on the occasion of Ray’s birth centenary.

You’ve written something that feels not just like knowledge, but like a quiet form of wisdom.